A major concert performer once complained to me that it was so difficult to play the war-horses. «It’s so hard to find a fresh approach,» he confided. I immediately had a contradictory reaction to this announcement. First I thought what an unusual person is sitting next to me, because the great majority of performers don’t think at all when they play their Pathetique or Moonlight Sonata or their Hungarian Rhapsodies. (The list of works can be enlarged or shortened, it doesn’t change the point.) These performers do not play what the composer intended, nor do they demonstrate their own relationship to the work, since their own relationship to it simply does not exist. Then what do they play? Just notes. Basically, by ear. It’s enough for one to start and all the rest pick it up. The list of literature played by ear nowadays has expanded to include Prokofiev’s sonatas and works by Hindemith, but the essential approach to the music by these stars has not changed as a result.

So while at first I was simply delighted by the self-critical announcement, my next thought was much calmer. And it went something like this: How can you complain that it’s hard to find a «fresh approach»? What is it, a wallet full of money? Can you find a «fresh approach» walking down the street—someone drops it and you pick it up? This pianist must have taken Sholom Aleichem’s joke seriously. You know, Aleichem said, «Talent is like money. You either have it or you don’t.» And I think that the great humorist is wrong here. Because money comes and goes, today you don’t have any, tomorrow you do. But if you don’t have talent, then the situation is serious and long-lasting.

Therefore you can’t find a fresh approach, it has to find you. A fresh approach to a work of music, as I have seen time and time again, usually comes to those who have a fresh approach to other aspects of life, to life in general—for example, Yudina or Sofronitsky.

But let’s return to my pianist friend who naively sought a fresh approach without changing his own life. I didn’t want to upset him with my considerations, why upset the man? I had to help him, and I remembered Glazunov’s advice about polyphony in playing.

And I said to him, «Why don’t you show the polyphonic movement in every piece you play, show how the voices move. Look for the secondary voices, the inner movements. That’s very interesting and should bring joy. When you find them, show them to the audience, let them be happy too. You’ll see, it’ll help a lot, the works will come alive immediately.»I remember that I made an analogy with the theater. Most pianists have only one character in the foreground — the melody — and all the rest is just a murky background, a swamp. But plays are usually written for several characters and if only the hero speaks and the others don’t reply, the play becomes nonsense and boring. All the characters must speak, so that we hear the question and the answer, and then following the course of the play’s action becomes interesting.

And that was my advice to the then already famous pianist, and to my great astonishment, he took it and acted upon it. Success, as they say, was not far behind. He had been considered merely a virtuoso without any particular depth in his playing, but now everyone was proclaiming how intellectual and deep he was. His reputation grew considerably and he even called me to say, «Thank you for a fortunate piece of advice.» I replied, «Don’t thank me, thank Glazunov.»

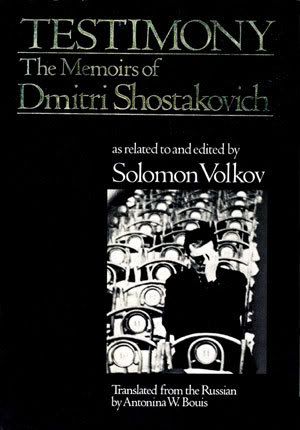

Testimony. The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. 1979